Häagen-Dazs and BBH rekindling their flame has got me excited

The ice cream brand and its famed agency achieved one of the great UK product launches 30 years ago. Will they have the same chemistry again?

The news that Häagen-Dazs has selected BBH to be its new agency of record made quite a few headlines last week. Younger marketers were probably left scratching their heads at the amount of coverage the announcement generated. After all, there are plenty of bigger brands than Häagen-Dazs and presumably loads of bigger-spending accounts. And rarely does a week pass without one brand or another switching agencies.

So why all the chatter? The answer is over 30 years old and can be traced back to an earlier era of brand building.

Häagen-Dazs was created in 1960 by Reuben and Rose Mattus. Despite the umlaut and the seemingly Scandinavian name, the Mattus family were first-generation Jewish Americans who lived in the Bronx. Apparently, Reuben stayed up all night concocting the most Danish-sounding brand possible, and despite this being quite literally nonsensical, the ice cream rapidly established itself in America and was eventually bought by US food giant Pillsbury in 1983.

Meanwhile in the UK, ice cream was having none of this fun. The category was bedevilled by low-cost, low-quality yellow shit (I’m generalising a bit here) that only really appealed to kids and a few adults on that very rare occasion when we experienced a hot summer’s day. The average Brit consumed a third of the amount of ice cream of their American cousins in the 80s.

But that weakness in the ice cream category became an opportunity for Häagen-Dazs. When Pillsbury decided to target the UK market in 1990, initial product tests on consumers sparked a series of important insights. Consumers were surprised by the opulent taste of cream and the indulgence that came with it. Many also began to question what was in the yellow shit they had been mistaking for ice cream thus far in their life. Indeed, so indulgent and pleasurable was the new experience, several consumers talked openly of feeding their partners with Häagen-Dazs and generally using it as a prelude to further intimacy. Things people hadn’t done with Lyons Maid or Funny Feet started to happen with Häagen-Dazs.

Follow Shania Twain’s lead and make sure product isn’t the forgotten P of marketing

A pioneering product launch

Pillsbury entrusted the UK launch to BBH; then, as now, just about as good an agency as you could hope to find. John Hegarty (the H in the name) was firing on all his creative cylinders and planner Nick Kendall was significantly ahead of his time and the strategic mastermind behind the launch.

What Kendall and his team did, quite brilliantly, was to build on the unusual insights from the product testing to craft one of the most effective brand strategies of all time. BBH ignored the traditional childish appeal of ice cream and instead aimed the brand at ABC1 adults, 25 years and older. It positioned the ice cream as the ultimate in intimate pleasure. And, to top things off, it opted for a tone of voice that was both adult and sensuous.

You can argue that other brands – not many, but some – have been positioned just as well and as tightly as Häagen-Dazs. But what made this launch so remarkable was how perfectly this simple strategy was executed through tactics. I used this as my go-to MBA case study for my class on execution from about 1996 until the point where it became older than some of my students and I finally took it out of circulation.

You can argue that other brands – not many, but some – have been positioned just as well and as tightly as Häagen-Dazs. But what made this launch so remarkable was how perfectly this simple strategy was executed through tactics. I used this as my go-to MBA case study for my class on execution from about 1996 until the point where it became older than some of my students and I finally took it out of circulation.

What made it so special? First and foremost, this was a proper full execution. Unlike so many launches that are 95% communications, BBH and Pillsbury joined the dots across all four of the Ps. And, unlike so many other launches, the team never took their eyes off that position of ultimate intimate pleasure and its adult and sensuous tone of voice. Everything, and I mean everything, sang from that same hymn sheet.

While marketing cannot save a terrible product, a great one will always be a huge factor in any marketing success.

It’s worth starting with product because so often we ignore the most important P in marketing and assume it is not a factor for marketers. I see too many dumb LinkedIn posts proclaiming that the brand with the best ads will always win the day over better products. This is bollocks. While marketing cannot save a terrible product, a great one will always be a huge factor in any marketing success. Especially if marketers understand the product and its connection with customers, and then link these truths into the rest of the tactical work.

‘It only works if it all works’: Marketers on ‘reclaiming’ the 4Ps

Adult, indulgent promotional campaign

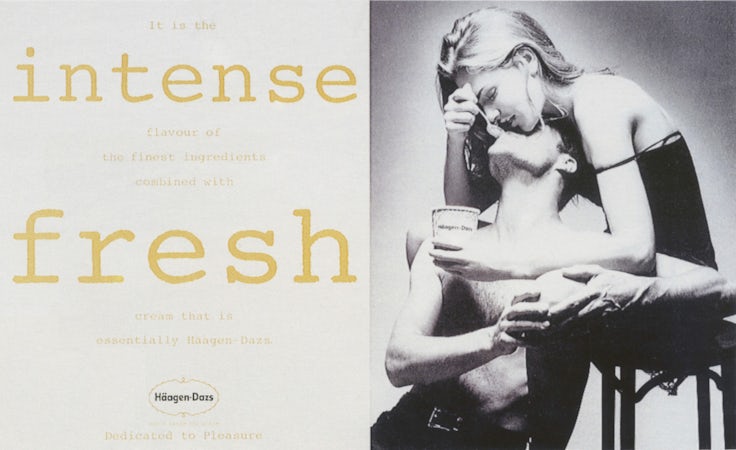

That’s exactly what BBH did. It made the inherent quality of the product an integral and interesting part of its advertising appeal. “It came out of how people talked about the ice cream,” Hegarty recalled in 2021 to an audience in New Zealand. “When they ate it, they said that in their head it was quite sensual. So, we created a campaign dedicated to pleasure. This was quite sexy ice cream.”

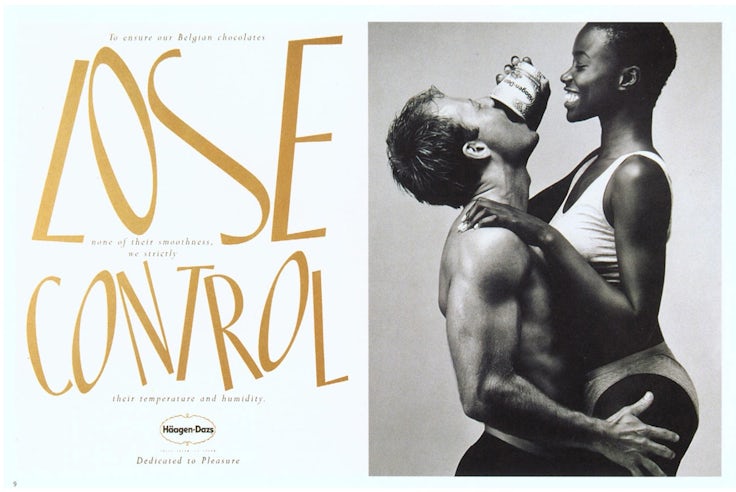

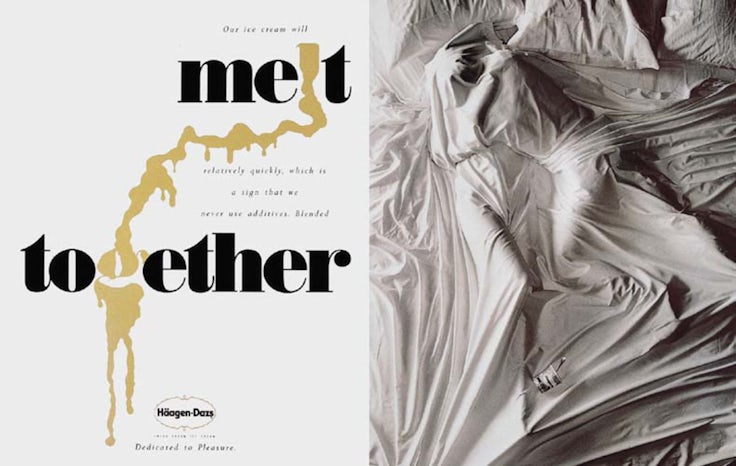

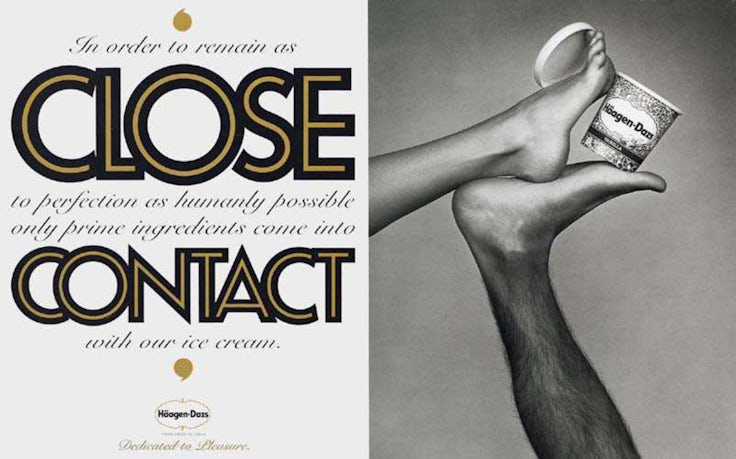

Copywriter Larry Barker scoured Pillsbury production manuals in which the company talked about the incredible care that went into the ingredients and manufacturing of Häagen-Dazs. He selected the most appropriate quotes and then, with a stroke of his pen, enlarged the words that also had an adult, sensuous connotation. This unusual copy was twinned on the other side of the page with photography from Jeanloup Sieff. Couples were shown using the product in adult, sensuous, pleasurable ways. Choosing Sieff, the great French fashion photographer, over the usual food photography options was a masterstroke because he was renowned for his sensual, arresting eye. And he looked at ice cream in an adult way.

That consistency with the brand position carried over into the media choices too. These were double-page glossy ads in the top fashion magazines, such as Vogue and Vanity Fair – something that had simply not happened ever before. But, again, the message was clear: this was adult, this was ultimate, this was indulgent.

That consistency with the brand position carried over into the media choices too. These were double-page glossy ads in the top fashion magazines, such as Vogue and Vanity Fair – something that had simply not happened ever before. But, again, the message was clear: this was adult, this was ultimate, this was indulgent.

The resulting images became probably the most iconic advertising of the early 90s. Despite barely achieving 5% share of voice during that first year, their impact and subsequent replay in coverage across all the mass media channels made a mockery of traditional ESOV calculations.

Branding through distribution

That mastery continued to the next P – place. Rather than simply open with Tesco, Sainsbury’s and the other big supermarkets, Pillsbury started with a whisper. At the very finest events there were Häagen-Dazs pop-up stores. The brand opened temporary cafés in upmarket locations like Covent Garden. As sales and awareness began to pick up speed, the team spread distribution across the higher-end independent grocers and also started to get the brand on the hotel menus of several of the better-quality hotel chains.

Only with advertising now driving sales, and the major grocery chains now clamouring for the brand, did Häagen-Dazs expand into full national distribution. It’s a trick still missed by so many brands. When you launch a new product, distribution is its brand image. Only later does it become sales and profit too. In the beginning, you want to find places and spaces that are the epitome of the brand position. The first time the consumer experiences your product, it should be the ideal on-brand experience.

Only with advertising now driving sales, and the major grocery chains now clamouring for the brand, did Häagen-Dazs expand into full national distribution. It’s a trick still missed by so many brands. When you launch a new product, distribution is its brand image. Only later does it become sales and profit too. In the beginning, you want to find places and spaces that are the epitome of the brand position. The first time the consumer experiences your product, it should be the ideal on-brand experience.

When you launch a new product, distribution is its brand image. Only later does it become sales and profit too.

If you manage to do this, three things happen. Your target consumer establishes a brand perception that can survive the generic challenges of being sold in Asda or Morrisons next to frozen sausages. Your brand can now service the growing consumer demand that your initial, limited distribution has created. And the noticeable brand appeal and growth gives you some (note: only some) power with the major supermarkets, who now want to stock you nationally.

It’s an old marketing joke that none of the big retailers find funny: how do you build brands in major supermarkets? You don’t. You do it before you start appearing there. Häagen-Dazs knew that it needed the big supermarkets. But it also knew that, paradoxically, advertising heavily and building the brand before it went into them was the right way to do things.

Ritson: Three axioms and three questions that summarise all of brand strategy

Luxury pricing

And all of this translated into a massive price premium. Partly because a premium price was another clear way to signal the adult and ‘ultimate’ nature of the brand. Partly because the brand had earned the right through masterful brand building to claim a premium. And partly because, if you believe in brand equity and understand marketing properly, it’s the only way to roll.

Pillsbury set the price of Häagen-Dazs at £2.99 a pot, an astonishing figure at the time. The UK was in a quite dreadful recession. It was £1 more than any of the competition in the UK. And in real terms it was significantly more expensive than the brand had managed to achieve back in the USA.

The brand still maintains a ridiculous price premium thanks to the work of BBH and the Pillsbury launch team more than 30 years ago.

Something else that signalled the Häagen-Dazs mastery with pricing was the total absence of discounts. No opening offers. No launch BOGOFs. I once told a brand manager who had launched his brand with a special 30% promotion that he had “slapped his baby a second after it had been born”. And I meant it. Nothing breaks your heart more than watching marketers soil their new products with a promotion barely before the brand lands on-shelf. A whole bunch of indignant marketers are now going to wah-wah on LinkedIn about why you have to run promotions because of big retail, consumer trial and host of other false justifications for their weakness. Tell it to Häagen-Dazs circa 1991.

The brand became market leader less than six months into launch year. And all these years later, the brand still maintains a ridiculous price premium thanks to the work of BBH and the Pillsbury launch team more than 30 years ago. I am writing this from the USA, where the RRP for a tub of Häagen-Dazs is $4.99. In Tesco this week it’s £5.40 – that works out at nearly $2 more than Americans pay, even with our current shitty exchange rate. Yes, big volumes are a pleasing reward for brand building. But the ultimate sign that you have cracked it is when those volumes occur at nose-bleeding price levels.

The brand became market leader less than six months into launch year. And all these years later, the brand still maintains a ridiculous price premium thanks to the work of BBH and the Pillsbury launch team more than 30 years ago. I am writing this from the USA, where the RRP for a tub of Häagen-Dazs is $4.99. In Tesco this week it’s £5.40 – that works out at nearly $2 more than Americans pay, even with our current shitty exchange rate. Yes, big volumes are a pleasing reward for brand building. But the ultimate sign that you have cracked it is when those volumes occur at nose-bleeding price levels.

Ritson: Tom Kerridge’s prices aren’t a rip-off if they’re what the market will pay

A tough act to follow

This enormous premium was born from astonishing marketing. Yes, a brilliant product with a wonderful bullshit name. But also from brilliant advertising. From clear insight. From spectacular and simple strategy. From a legendary launch that did everything right. And from proper marketing tactics that spanned product, promotion, place and price and united them into a phalanx of marketing excellence, the like of which we have not seen again.

And that’s why the news that Häagen-Dazs had hired BBH made such big headlines last week. For anyone old and in-the-know and in marketing, these two did it better than anyone else and there is a chance – just a chance – that sexy lightning might strike twice.

I spoke with the team at General Mills on Friday. The company bought Pillsbury years ago and Häagen-Dazs is its baby now outside of the US. I was hoping they were going to prove the point about advertising wear-out being a myth and actually replay the wonderful ads of 1991 to a whole new market. But Gini Mines, Häagen-Dazs global brand experience director, let me down gently.

She made some pretty good arguments in favour of new creative. But I pointed out that this would put her under a bit of pressure, given she was now making the sequel to The Greatest Launch of All Time. “I like that kind of pressure,” she smiled, before hanging up on Zoom. It was the ultimate, adult way to end our chat. And I am left with hope for Häagen-Dazs.

Mark Ritson is five times winner of the PPA Columnist of the Year award and currently the British Society of Magazine Editors Business Columnist of the Year. A former marketing professor, he now runs his wildly successful Mini MBA in Marketing in an ultimate, sensual, adult kind of way.