Do you have a marketing philosophy?

From Delony Sledge to Fernando Machado, marketers with a coherent brand philosophy produce better and more consistent advertising.

Do you have a philosophy for how marketing communications work for your brand? I don’t mean a strategy or plan. I mean a vision that’s articulated simply, compellingly, inspiringly.

Do you have a philosophy for how marketing communications work for your brand? I don’t mean a strategy or plan. I mean a vision that’s articulated simply, compellingly, inspiringly.

For most marketing people the honest answer is probably no, although I suspect it’s a bit more common amongst marketers at the ‘brand’ end of the marketing continuum than the ‘performance’ end.

Today’s bias for the practical over the philosophical may be partly to blame – which, whilst maybe great for getting a million things done in the short term, isn’t so good at helping us get the right things done over the longer term. But having a philosophy has practical benefits: it can help bring focus and consistency.

The philosophy articulated in 1959 by Coca-Cola’s legendary advertising director Delony Sledge is a powerful example. In a letter to J. Paul Austin, then president of The Coca-Cola Export Company, Sledge wrote:

“If we, in presenting Coca-Cola to our consumers, are content to do ordinary things in an ordinary way, we must of necessity be content to become, and remain, an ordinary product.

“If, on the other hand, we determine to do extraordinary things in an extraordinary way, we are perfectly safe in assuming that we will create, in the minds of our consumers, an image of an extraordinary product.

“Many years ago in the United States, Coca-Cola chose the latter route, and I believe the character and prestige enjoyed today (and maintained even in the fact of fiercest competition) is the result of this choice.”

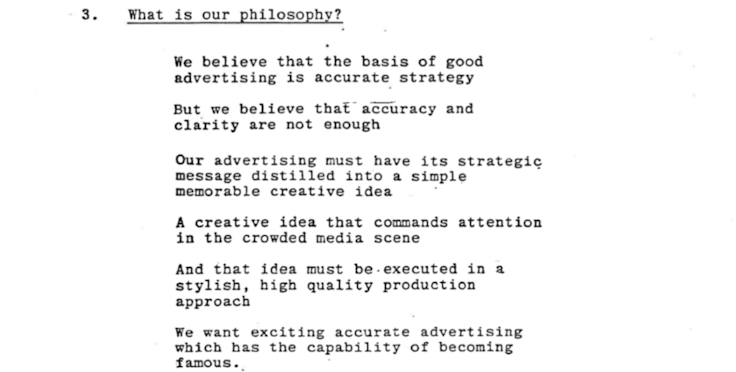

Or take this precisely articulated section of a 1982 pitch brief by Whitbread Beer Company (now AB InBev) to ad agency BBH. It’s not simply a brief for an ad campaign – it sets out their entire belief system:

Most client briefs today tend not to include anything as clear-sighted or inspiring about how a brand’s communications should work in their totality. Fragmentation and specialism in both the client and agency worlds probably hasn’t helped.

Perhaps the now ubiquitous sales funnel has played a role too. If briefs only ask for approaches to a specific layer of the funnel (to drive awareness, consideration, conversion, loyalty or advocacy), maybe developing a perspective on how the layers should work as one coherent system is bound to get less attention.

Perhaps marketers are expecting their brand guidelines or marketing playbook to play this role. But while these may aid consistency and provide practical tools, they’re usually lacking much in the way of vision or inspiration.

The philosophical impasse

If more marketers had a coherent philosophy, I suspect agencies would be much better equipped to deliver work that meets or beats expectations.

Agency people love CMOs with a strong point of view on this – it’s so much easier than having to guess, having to find common ground between stakeholders with differing perspectives, or having to tell them what their perspective should be.

I once had a senior client team including a brand purpose lover, an emotional storytelling fan, a Byron Sharp evangelist, and someone who just wanted ads that made people laugh. There was no philosophical coherence to their respective positions. The overlapping area of the Venn diagram in which the brand’s communications needed to play was impossibly tight.

Our work became inconsistent, performance deteriorated, and an agency with a vision compelling enough to cut through the philosophical impasse won the business, and have since gone on to bring coherence, consistency and creative excellence.

Someone with a coherent philosophy that’s plain to see from his output across multiple brands is ex-Dove marketer, Burger King and now Activision Blizzard CMO, Fernando Machado. His pinned tweet on Twitter reads: “I stumbled on this picture of something I wrote back in 2013 when we were deploying Dove Real Beauty Sketches. Still relevant today as it was 7 years ago.”

I stumbled on this picture of something I wrote back in 2013 when we were deploying Dove Real Beauty Sketches. Still relevant today as it was 7 years ago. #marketing #advertising pic.twitter.com/39CvhLj7rB

— Fer Machado (@fer_machado123) April 16, 2020

Whatever your views on the work Machado did at Burger King, you can’t deny it was clearly driven by a singular vision of what he believes works. Many marketers have individual creative ‘hits’; having a consistently applied creative philosophy like Machado’s gives you a greater chance of keeping those hits coming year after year, for different brands, and earning the career progression that’s likely to follow.

To be able to articulate your own advertising philosophy, you have to be more actively conscious of your own fundamental beliefs about what works best than most of us tend to be. You need to know which marketing principles, ideas and concepts you believe in, the ones you tend to build your plans around and return to time and again. And you need to be just as clear about the things you don’t believe in.

If you’ll excuse me for jumping from the philosophical to the profane, one way to think about this is to ask yourself what your kiss, marry, or kill of marketing ideas is.

My answers – the things I believe in most unwaveringly – are: creativity, reach, attention, fame, emotion, distinctive brand assets, mental availability, bothism. The things I’d consign to marketing’s Room 101 include the label ‘performance marketing’ (all good marketing is performance marketing isn’t it?), brand love (sounds like a nice idea but isn’t actually a major driver of brand growth) and brand purpose (when it’s seen purely as an advertising tactic rather than baked into a business model).Marketers urged to ignore ‘false boundaries’ of brand and performance

If pushed for a final answer I’d say my choices would be fame, bothism and brand love.

Our own individual answers to this question reflect our identities as marketing people and will be shaped by everything we’ve experienced in our careers. Mine are being shaped by the journey I’m on, from the holding company creative agency world to Jellyfish, a new era full-service communications company, which is opening my eyes wider than ever to the ever-increasing array of options available to solve any given marketing problem.

I know my choices have changed in the last few years and I’m sure they’ll evolve over the next few years, given the new ideas, tactics and tools I’m now being exposed to.

Sniffing out the snake oil

Most of us are probably too busy doing the job to ever take much time to think about it. A lack of formal marketing training covering the marketing fundamentals doesn’t help. And neither is the on-going tactification of marketing, an increasing ‘modern marketing myopia’, that I wrote about recently.

Marketing is an incredibly broad church and we have an infinite variety of different philosophical, strategic and tactical options available to us if we open our eyes and our minds to them. People being able to have their own distinct points of view is part of the joy of what we do. There is never only one way or solution, there are always lots – many effective, many less effective.

The philosophical position you take will tend to be heavily influenced by the most influential marketing leaders and thinkers in your own corner of the marketing world.

If more marketers had a coherent philosophy, I suspect agencies would be much better equipped to deliver work that meets or beats expectations.

Tom Roach

If your experience is primarily in brand marketing or FMCG, and you’re from the UK or Australia, you’ll probably have adopted some of the academia-honed ideas of Byron Sharp and the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute. If you look more to the US tech and VC world, it might be the brand and advertising-sceptical perspective of Scott Galloway, or perhaps the organic social content-obsessed Gary Vaynerchuk.

But rather than just believing what your own gurus or particular tribes believe, maybe we should make up our own minds more deliberately, less passively, with a healthy dose of scepticism and a far broader understanding of the wider options available.

It would benefit all of us to question the validity of the new ideas that we’re sold overtly and covertly every day (and practically every piece of marketing content you read is selling you something).

As Paul Feldwick talks about in his superb book ‘The Anatomy of Humbug’, a surprising number of the ideas we use every day in advertising (such as the ‘USP’ popularised by Rosser Reeves of The Ted Bates Agency in the 1960s) were originally created to sell an agency’s services, and this will always be the case.Could your brand benefit from the ‘diversity dividend’?

In fact anyone who insists there’s only one way to solve your problem isn’t trying to solve your problem, they’re probably trying to sell you their solution. We all need to be better equipped to judge which of the new ideas we’re exposed to were designed to promote a particular company. Which are sound, and which are snake oil.

So if you don’t have your own advertising philosophy worked out and written down, perhaps you should give it a go. Applying some self-knowledge, Socrates’ maxim ‘know thyself’, is a good way to start.

Because even practitioners can benefit from a little philosophy.

Tom Roach is vice-president of brand planning at Jellyfish

Comments